Parenting with Complex Ptsd

This article was posted on our original blog at Healing from Complex ptsd, December 8th 2020.

Sherry Yuan Hunter

No, that’s not true. I have a lot of patience for a lot. I have the capacity to do a lot, put up with a lot, and fix a lot. However, there were specific things that seemed to trigger an outburst of anger, fear, and vengeance that could be seen to be an over-reaction. And yet, it was usually over something legitimate.

How can it be an over-reaction when, very logically and rationally of course, I was right!?

I’ll give you an example: We were ‘trying’ to teach my tweens to do housework with us. I don’t want to raise lazy bums who cannot do anything and who end up at university not even knowing how to do laundry. Whoops, yes, that was me. There was so much I didn’t know how to do when I was alone in another country at 18, trying to get good grades and not knowing how, and trying to manage my life, and — well, not knowing how. Figuring out how to make friends, and feeling like I was failing at that too. Anyway — I digress — back to the story of getting our boys to help with housework…

I was patient, honestly! We nagged. We cajoled. We reminded. “After. Dinner. You. Sweep. The. Floor. Then. You. Wipe. The. Table. And. YOU. Do. The. Dishes. And. Throw. Out. The. Garbage.” I’d enunciate through gritted teeth. One day, I lost it. I yelled. I guilted them about how hard I work to make money for them and how I’ve told a million times to do this. They both watched me and, in slow motion, I saw myself grab the broom and hit the chair. Hard. Over and over. I raised it in anger and whacked it against the pantry door. The bottom brush part of the broom broke off! We all looked at the mark it left on the door and they looked at me in horror. I looked back at them in horror — still breathing hard from being angry. My slowly eyes widened at the realization of the physicality of what I was doing and, more importantly, to their developing minds and spirits.Normal text.

That was a defining moment for me as I realized that I was ironically behaving like a victim and bullying my children. Oh my goodness, I was behaving like a bully to get my way! My frustrations stemming from my fears and hopelessness triggered something deeper. It was trying to get control of the situation, but felt that the only way to do that was to have a temper tantrum.

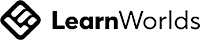

Take a peek at this chart and see if you identify with what is described in that first column, like I did.

I didn’t know I was responding from a place of fear and past trauma. I just thought that I was getting angry about something that was legitimate. Even they agreed that my issue was legitimate. But then they were prepared to internalize my behaviour as reasonable. That was where I had to draw the line. So, after taking a few deep breaths, I told them, Hey, I’m angry. I’m super angry. But the anger has nothing to do with you. No one deserves to be yelled at like that. You did not deserve that. I lost it, and that’s on me. I still think the reason why I got mad is actually still a legitimate issue and I’d like you to keep that in mind, but no one, not a single person, deserves to be yelled at like that. You should never let anyone yell at you like that, not me, not anyone. I am so sorry for yelling at you and even breaking that broom.

The good news is once I started realizing that I wanted to change and committed to the idea that I did not want to pass on my traumas to my children, I could get the kind of help I needed. The not-so-great-news is that it’s a lot of hard work and there’s a lot of taking steps forward and backward. I’d like to say that magically I no longer yelled at them, but it took a few more triggers before I was able to stop the yelling from coming out of my mouth.

It helped that my hyper-vigilant kids would sometimes pause and say, Hey Mommy, are you getting stressed? Are you mad? You look like you’re mad. They were saying this at times when I was just sitting there with a furrow in my brow, thinking about what else to put on my grocery list. I knew that I did not want them walking on eggshells around me or being constantly worried that I was going to blow my top.

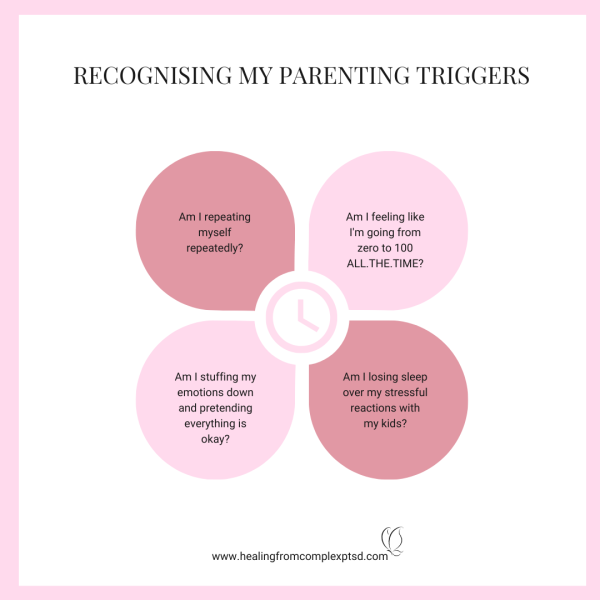

Reading parenting books telling me to be better was triggering, only I didn’t realize it. I just kept beating myself up for being a bad parent. Now, I’m not a bad parent, I tell you, I’m pretty good. But, as a human being, I had some bad moments. As someone with CPTSD, those moments would trigger spirals of self-loathing ending with I can’t make my life work. Work triggers did the same. If I only had to deal with one or two triggers a day, I could manage for a while. But dealing with a few at work and then a few at home on the same day was turning into a full-blown breakdown.

Parenting is difficult. Suffering from CPTSD can be debilitating. Trying to be a great parent whilst dealing with CPTSD is overwhelming. As parents, we can’t stop taking care of things and as CPTSD survivors we need to take care of ourselves. Know that you’re not alone and that there are people who want and can help.

Courses

Let's Create Generational Change Together

To support this goal, Healing from Complex Ptsd allows you to:

- Access professional education and business support from industry leaders

- Learn a results driven approach to CPtsd recovery

- Discover a full library of ready to use tools and resources

Popular courses

Terms and Conditions

Developmental Trauma Self-Check

Over the past 12 months, how many and how often have you noticed:

-

I work hard to hold it together in public, then crash in private.

-

I struggle to name what I feel until it overloads me.

-

I say yes to keep the peace, then feel resentful or empty.

-

I feel loyal to people who do not treat me well.

-

I lose time or feel foggy when stressed.

-

I avoid closeness or over-attach quickly, then panic.

-

I find it hard to trust my own judgement.

-

I feel shame when I try to set boundaries.

-

I need external approval to feel steady.

-

I push through fatigue instead of pausing.

How to use this:

0–3 items often: you may be using a few survival patterns.

4–7 items often: consider paced support to rebuild safety and choice.

8–10 items often: a trauma-trained professional can help you restore stability and connection.

Brain Impact Self-Check

Over the past 12 months, how often have you noticed:

-

My mind jumps to what could go wrong, even in safe moments.

-

I find it hard to remember recent details when I am stressed.

-

Decisions feel risky, so I delay or avoid them.

-

I forget good experiences quickly and dwell on the bad.

-

I feel numb or overwhelmed, with little in-between.

-

I lose words when emotions rise.

-

I misread neutral faces or tones as negative.

-

I struggle to notice body signals like hunger, tension or breath.

-

I do better when someone I trust is nearby.

-

I feel different “versions” of me in different settings.

How to use this:

0–3 often: some protective habits; gentle self-care may help.

4–7 often: consider trauma-trained coaching to build daily brain skills.

8–10 often: a paced, brain-based plan can restore clarity, memory and confidence.

For formal assessment, use recognised measures:

-

ACE-IQ or ACE-10 for adversity history (education only on public pages).

-

ITQ (International Trauma Questionnaire) for ICD-11 PTSD/Complex PTSD.

-

DERS for emotion regulation, DES-II for dissociation, PCL-5 for PTSD symptoms.

-

PHQ-9, GAD-7 for mood and anxiety; OSSS-3 for social support.