Hypersexuality

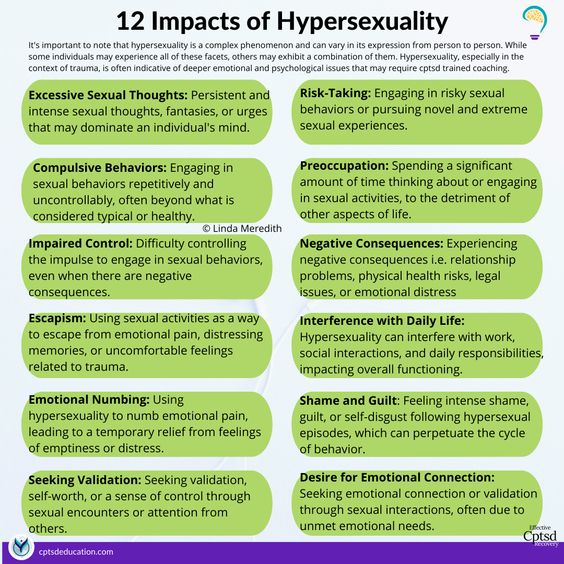

The link between these early adverse experiences and hypersexual behaviors isn't just coincidental; rather, it often reflects deeply ingrained emotional and psychological patterns that may have evolved as coping mechanisms. In this blog post, we'll explore the intricate relationship between childhood developmental trauma and hypersexuality, shedding light on how one can influence the other and what can be done to navigate this sensitive terrain.

Whether you're a coach, a healthcare professional, or someone trying to understand this issue more deeply, read on to gain insights into this multifaceted topic.

In the context of childhood developmental trauma, healthy sexuality could be understood as the ability to engage in sexual expression and relationships in a manner that is affirming, respectful, and emotionally safe, in spite of past adverse experiences. For those who have experienced childhood developmental trauma, the pursuit of healthy sexuality often entails a process of unlearning harmful beliefs or behaviors and replacing them with ones that foster consent, mutual respect, and emotional well-being.

Understanding healthy sexuality, therefore, isn't just about the physical act of sex, but encompasses emotional intelligence, self-awareness, and effective communication. It is about recognizing and respecting one's own boundaries and those of others, something that can be significantly challenging for those impacted by developmental trauma. In this light, healthy sexuality becomes not just a personal achievement but also a relational one, reflecting a state of well-being in the individual and in their interactions with others.

Individuals who have experienced developmental trauma may struggle with issues such as establishing boundaries, understanding bodily autonomy, or recognizing the nuances of consent. Their concept of sexuality can often be entangled with past experiences of coercion, exploitation, or neglect, which complicates their path toward a healthy sexual identity.

Education and coaching can play a crucial role in guiding people toward a healthier understanding of sexuality. This involves not only factual education about sexual health but also the emotional and psychological aspects, such as promoting self-compassion, addressing shame and guilt, and empowering individuals to make informed choices that align with their values and needs.

In summary, healthy sexuality in the context of developmental trauma is an ongoing process that often requires both unlearning detrimental beliefs and adopting new, healthier patterns of emotional, social, and physical interaction. It involves the integration of various aspects of the human experience — emotional, social, cultural, and physical — in a way that is consensual, respectful, and free from the impacts of past traumas.

Courses

Let's Create Generational Change Together

To support this goal, Healing from Complex PTSD allows you to:

- Access professional education and business support from industry leaders

- Learn a results-driven approach to CPtsd recovery

- Discover a full library of ready-to-use tools and resources

Developmental Trauma Self-Check

Over the past 12 months, how many and how often have you noticed:

-

I work hard to hold it together in public, then crash in private.

-

I struggle to name what I feel until it overloads me.

-

I say yes to keep the peace, then feel resentful or empty.

-

I feel loyal to people who do not treat me well.

-

I lose time or feel foggy when stressed.

-

I avoid closeness or over-attach quickly, then panic.

-

I find it hard to trust my own judgement.

-

I feel shame when I try to set boundaries.

-

I need external approval to feel steady.

-

I push through fatigue instead of pausing.

How to use this:

0–3 items often: you may be using a few survival patterns.

4–7 items often: consider paced support to rebuild safety and choice.

8–10 items often: a trauma-trained professional can help you restore stability and connection.

Brain Impact Self-Check

Over the past 12 months, how often have you noticed:

-

My mind jumps to what could go wrong, even in safe moments.

-

I find it hard to remember recent details when I am stressed.

-

Decisions feel risky, so I delay or avoid them.

-

I forget good experiences quickly and dwell on the bad.

-

I feel numb or overwhelmed, with little in-between.

-

I lose words when emotions rise.

-

I misread neutral faces or tones as negative.

-

I struggle to notice body signals like hunger, tension or breath.

-

I do better when someone I trust is nearby.

-

I feel different “versions” of me in different settings.

How to use this:

0–3 often: some protective habits; gentle self-care may help.

4–7 often: consider trauma-trained coaching to build daily brain skills.

8–10 often: a paced, brain-based plan can restore clarity, memory and confidence.

For formal assessment, use recognised measures:

-

ACE-IQ or ACE-10 for adversity history (education only on public pages).

-

ITQ (International Trauma Questionnaire) for ICD-11 PTSD/Complex PTSD.

-

DERS for emotion regulation, DES-II for dissociation, PCL-5 for PTSD symptoms.

-

PHQ-9, GAD-7 for mood and anxiety; OSSS-3 for social support.