The amygdala, our brain's emotional watchguard, can trigger anxiety or panic attacks without warning. Such episodes may occur in the midst of an ordinary day—even during pleasurable activities like a gym session—manifesting with symptoms that resemble petit mal seizures, including involuntary jerks and sensations of shock. This can force an immediate and bewildering confrontation with our inner state of alarm.

Those living with Complex PTSD will find these abrupt and intense emotional responses all too familiar. For a clearer insight into these brain processes, educational resources like the provided video explain how the amygdala retains unprocessed childhood trauma, leading to overwhelming sensory experiences that initiate an anxiety attack. Subsequently, this triggers a disconnection from the prefrontal cortex's logical faculties, engaging the primal fight, flight, or freeze response as a means of survival.

Understanding our trauma's impact is one thing; learning to effectively manage our responses to it is another. To do this, we must adopt practical and consistent actions to diminish the power and duration of these triggers.

Breathing as a Foundation for Stability

A foundational practice is to cultivate a deep awareness of our breathing patterns. Short, shallow breaths are a common response to being triggered. By practicing extended inhalations and exhalations—each lasting five seconds—we can train our bodies to respond to stressors with more resilience. This form of practice serves a dual purpose: it aids in calming the mind for better sleep and equips us with a coping mechanism for stress.

Nurturing Present-Moment Awareness

Rest and hydration are essential following an anxiety attack, serving to soothe the brain and body and to reset our physiological state. In the throes of an attack, even a simple act of drinking water can serve as a grounding exercise, reconnecting us with the present moment.

Affirming Safety Against Sensory Overload

When sensory input sends a false alarm of danger, reaffirming one's safety becomes a key strategy. By methodically reassuring ourselves through sensory engagement and cognitive reassurance, we can dispute unfounded fears and begin to feel secure in our environment. This strategy also involves practicing the aforementioned breathing technique to alleviate physical tension and foster a sense of calm.

The journey to rewire our brain's response to past trauma is neither quick nor easy, but it is certainly possible. Sharing personal experiences, such as the initial need to withdraw from the gym, illustrates the validity of respecting one's healing process. As one progresses, such coping mechanisms can become integral to facing and overcoming anxiety in real-time.

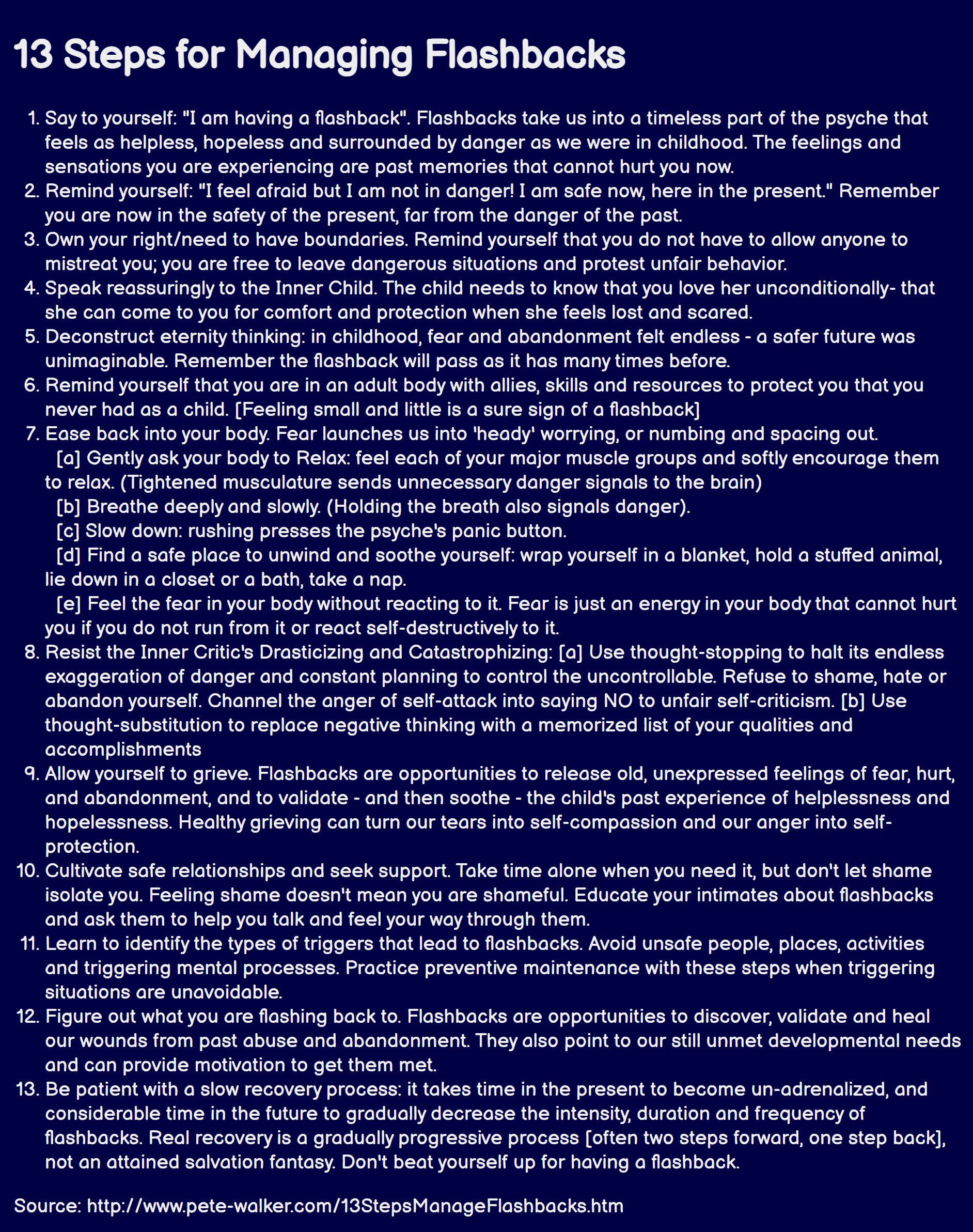

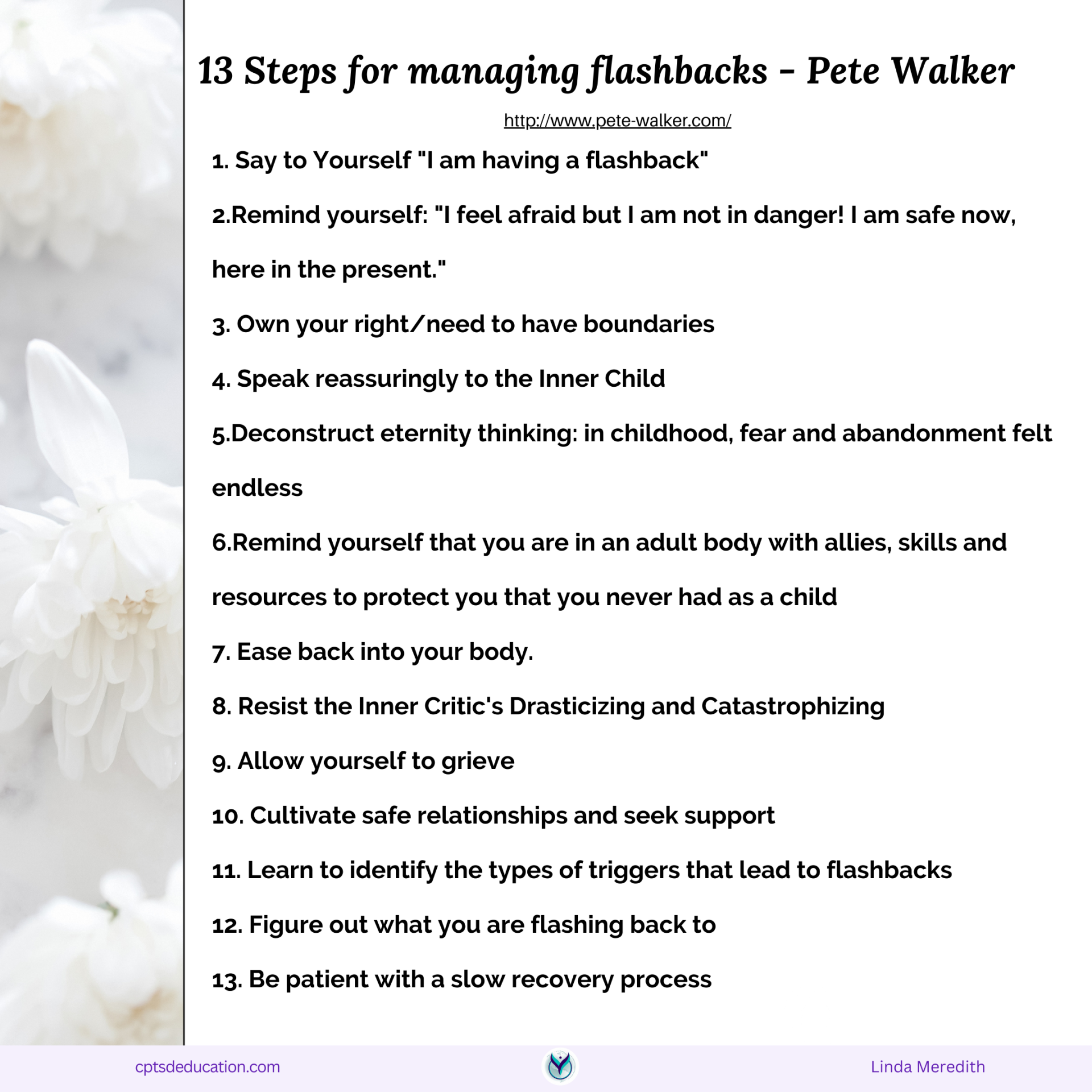

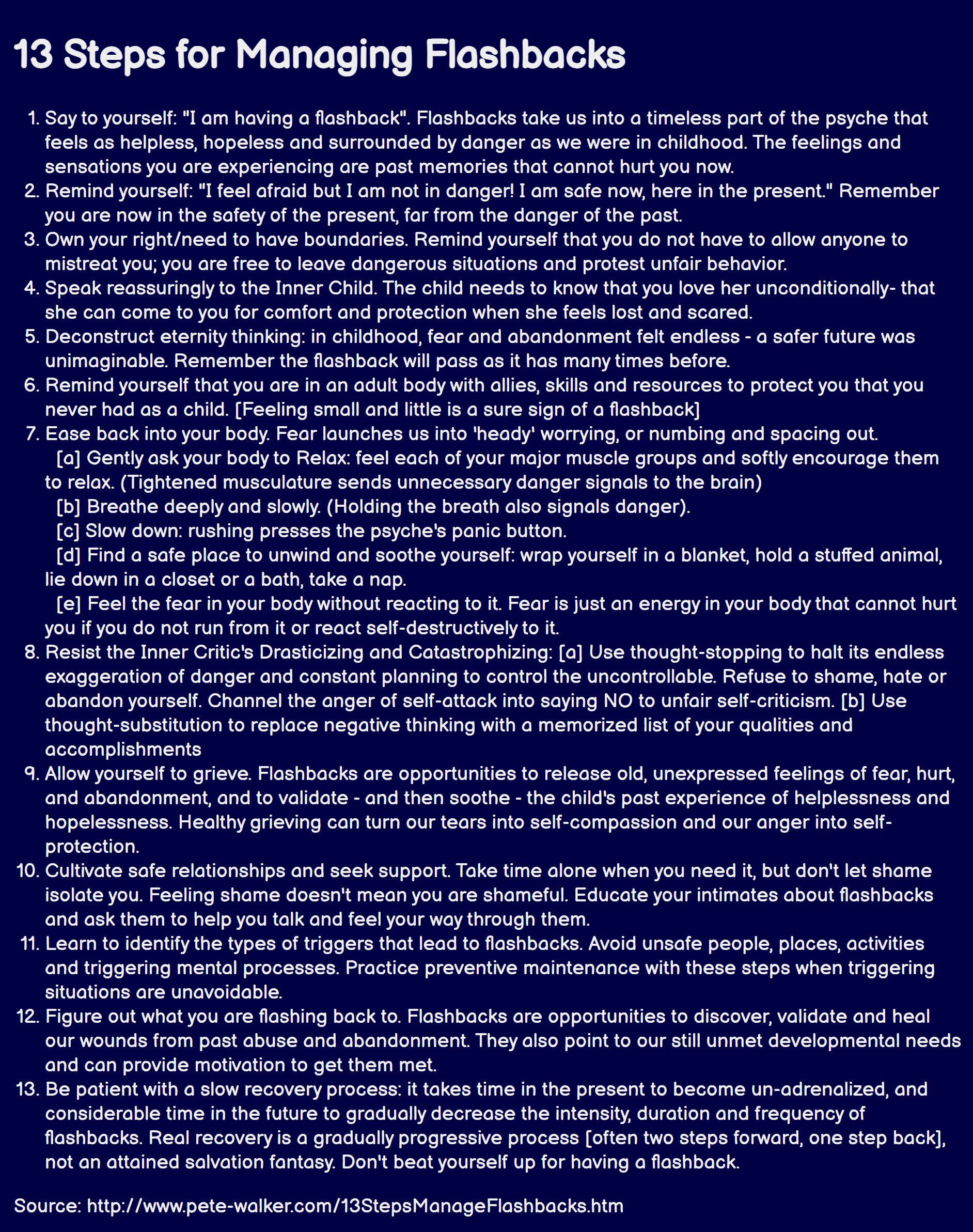

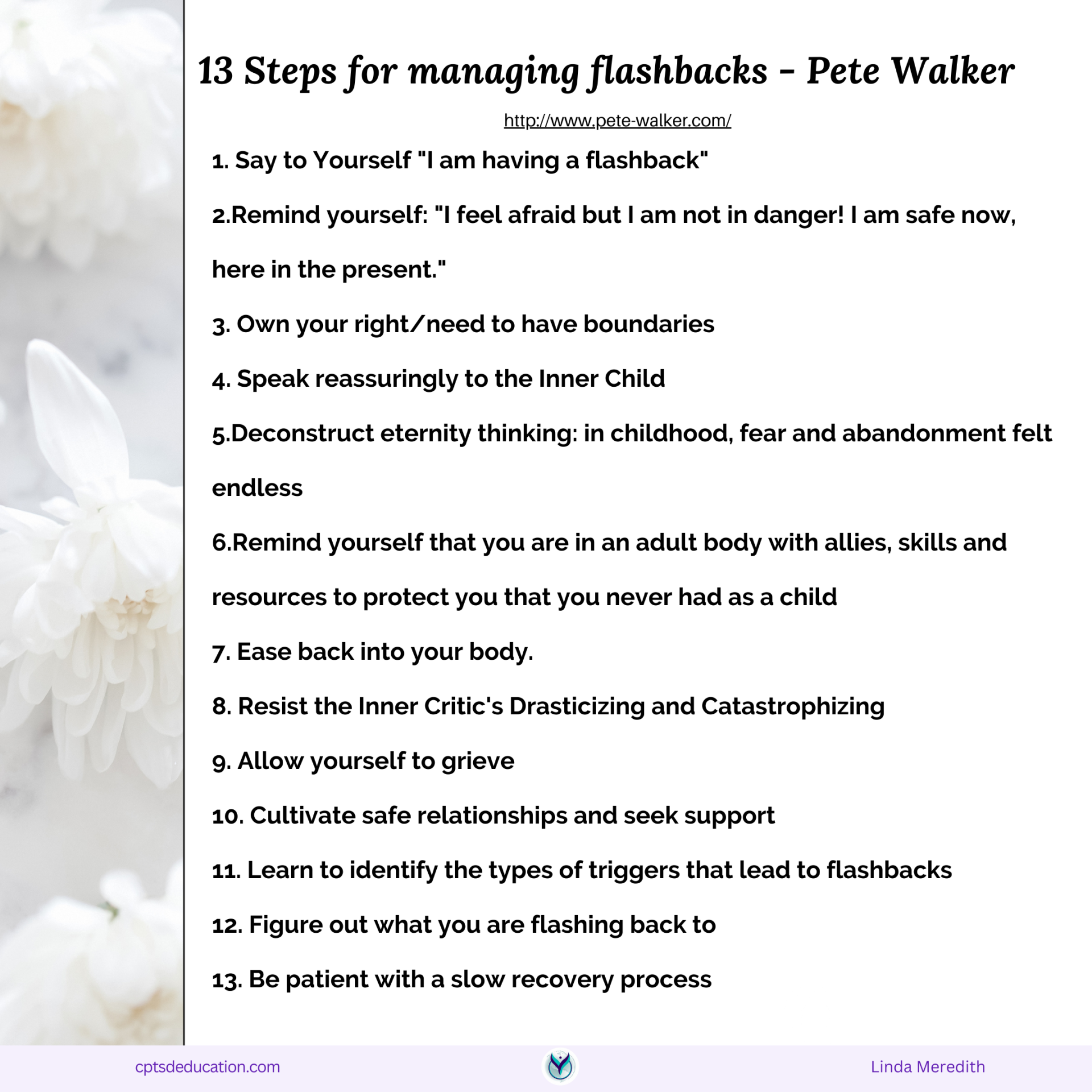

Implementing structured approaches like Pete Walker's '13 Steps for Flashback Management' can significantly improve one's ability to detect and manage flashbacks, reducing their disruptive effects. Accessing and utilizing such resources provides valuable support in this aspect of recovery.

Building awareness gradually can incrementally liberate an individual from the constraints of their trauma responses. A disciplined approach to daily practice promises a transformative experience over time, significantly altering one's quality of life for the better.

In conclusion, although retraining our brain away from past traumas to adapt to current realities is a time-consuming endeavor, the empowering outcomes warrant the commitment. It is an investment in a future where one's agency and well-being are restored.